Transformational Journeys

Read case studies and parent testimonials to learn how our revolutionary approach has led to transformational growth for our students

Following are just a few of the student transformations that we have helped students to realize since we first began developing new educational approaches in 2019. Find out more here, on our blog and in our parent testimonials. Scroll down to learn more about the research-backed methodology behind our results.

Check back for more case studies to come!

Grade level: Middle school

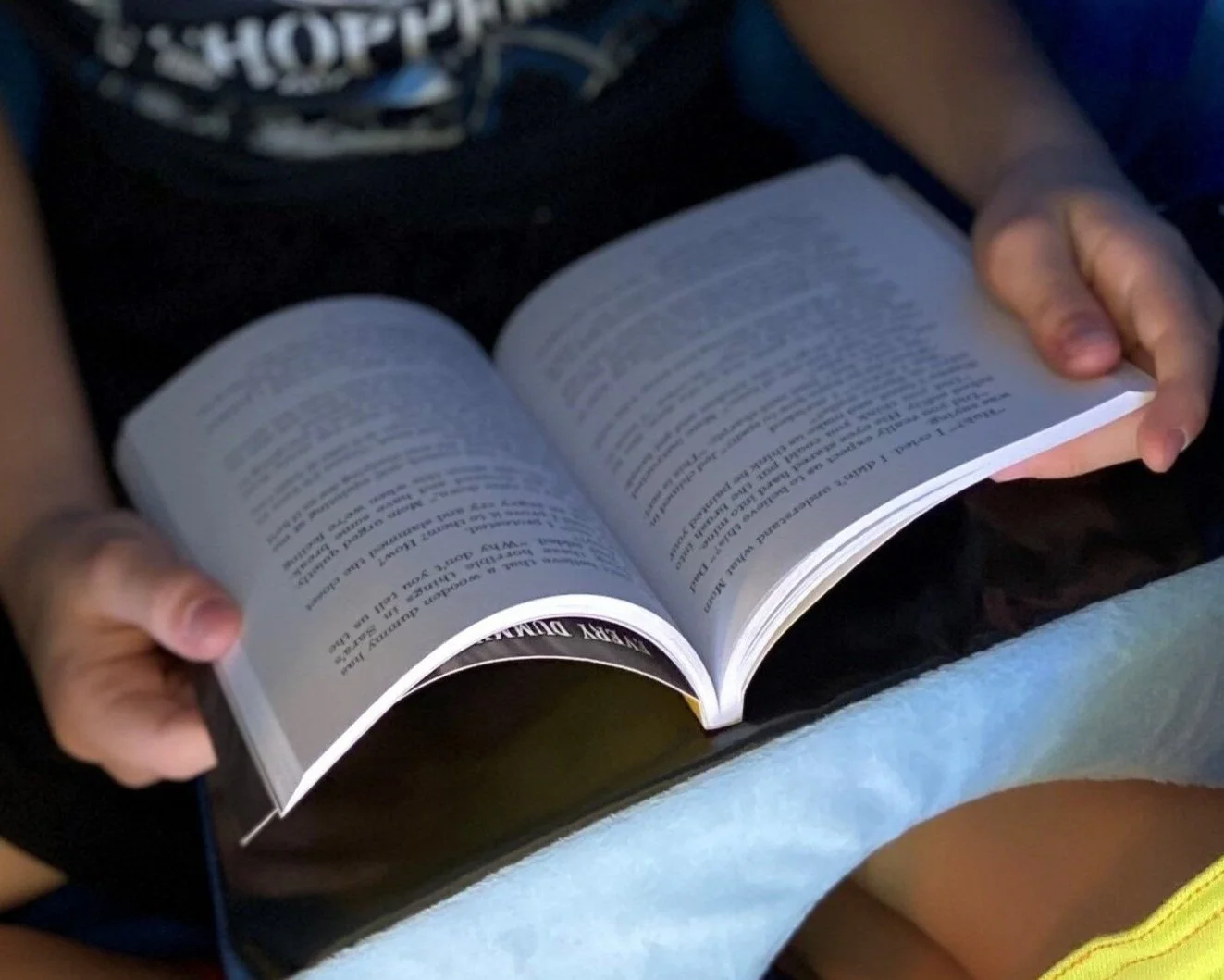

The Success: In September, they couldn’t read more than a paragraph without losing track of what the words even mean, and couldn’t spell more than their own name without someone spelling it letter for letter. And they were brilliant. The file simply said, “refuses to do non-preferred tasks.” We discovered that entering a classroom was one of those “non-preferred” activities, and they were willing to do just about everything to avoid it. By February, they were independently reading 45-60 pages per week and by April they independently drafted a short story while typing it. By June, they understood themselves as someone who actually belonged in a school building.

The Obstacles: The first challenge was the lack of any incoming information, and the fact that they were willing to go to fairly extreme lengths to conceal that information from us (as we learned when we had to conduct full-on negotiations to go to class!).

The Strategies: Using our very close teacher connections and trauma-informed approach, they allowed us to see their profound difficulties reading and writing. Close observation and assessments by our clinicians revealed a profound dyspraxia, derailing all the cognitive resources they needed to engage in reading and writing. Further investigation revealed that they had retained primitive reflexes that derailed their ability to engage in core academic processes. Our licensed physical therapists gave them daily exercises integrating those reflexes into increasingly functional gross motor patterns, which formed the basis for our occupational therapist’s work teaching his brain how to reliably track back and forth across the page with his eyes, correcting for the ocular-motor coordination difficulties that were holding back his ability to read.

Favorite Project: “How can we create a theme park with scientifically-possible rides?”

Grade Level: 9th-12th grades

The Success: He joined us with severe social and academic anxiety, ADHD, brain fog and visual challenges—and in the first months of a medical crisis that would threaten his life. Five years later, he’d become our 1st graduate, and went on to study architecture at the college of his dreams, where he’s thriving academically, quickly built himself a strong group of friends and is managing even his complex medical needs independently.

The Obstacles: A prolonged life-threatening medical illness had left this student uncertain deeply uncertain about his future, unpacking medical trauma and the social isolation it had created, and generally struggling to find the motivation and growth mindset to dream, let alone work towards making that dream come true. At the same time, the medical crisis had impacted his cognitive skills, expressive language, executive function skills and core physiologic functioning. In short, he was in the sub, sub-basement with graduation just a few years out—so at that point college wasn’t even on the radar.

The Strategies: This one took everything we’ve got! Our physical therapists supported him through the long months on the way to diagnosis of a tethered spinal cord, patiently teaching him how to monitor and report his symptoms so he could meaningfully participate in his medical care. Post corrective surgery, they quarterbacked his physical recovery while his academic team quarterbacked recovery of lost learning time—and our neuropsychologist kept the physical and academic recoveries in balance with his social-emotional recovery as well. By the time he graduated, the communication, organizational and social difficulties were no longer discernable, leaving a confident and resilient young man ready for new adventures defined by his gifts, not his challenges.

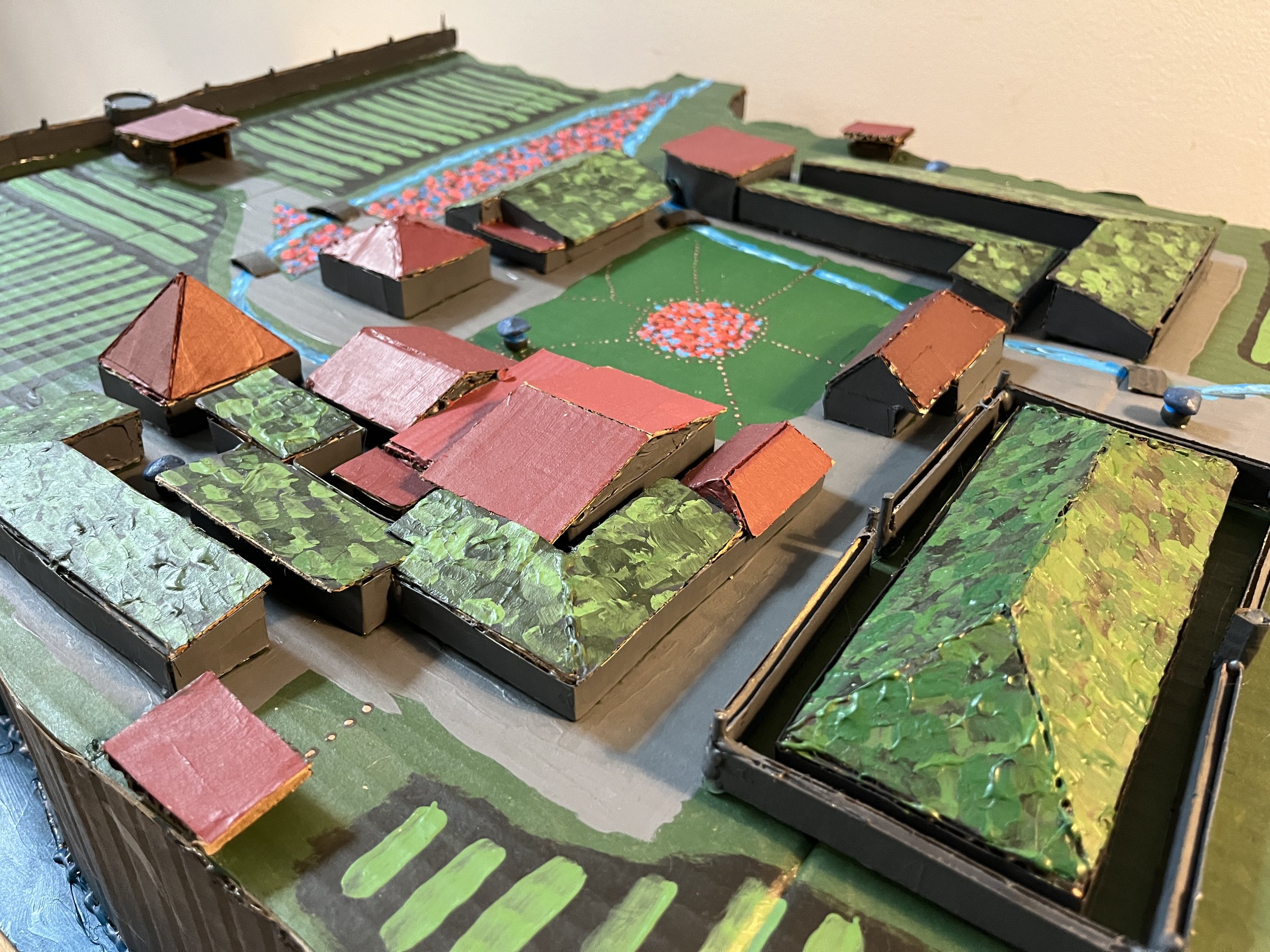

Favorite Project: “How can we envision a democratic community in the years 1202-1204, in Normandie, France?”

Grade Level: 3rd grade

The Success: Leaving the public school, he had great decoding strategies but would give up and toss the book after 5 minutes. His strong phonological skills meant that he didn’t meet the criteria for dyslexia, so his mom was told “we can see how bright he is, so if he wanted to read he could.” An outside assessment revealed that despite his strong decoding strategies, he had no ability to remember sight words—thus the fatigue after 5 minutes. 6 weeks into our Neuroplasticity Interventions, he was reading above grade level, for pleasure.

The Obstacles: Listening more closely to the way he read, we realized he would use a different decoding strategy each time a sight word came up, even if it appeared 2 or 3 times on the same page, and each time he’d pronounce the word differently. From this we realized that he had an orthographic processing error that was driving a specific learning disability in reading that is sometimes termed “surface dyslexia.” A review of his data revealed that he was 3 years above grade level in all of the skills required to read except orthographic processing, where he was 3 grade levels behind—thus preventing him from ever finding books “on his reading level.” Meanwhile, his experiences in public school had convinced him both that he would never be able to read and also that he would get in trouble if he “refused” to do so, generating a trauma that deeply impaired the growth mindset that is essential to learning. Moreover, this reading difficulty was just one of several learning and social-emotional obstacles this child had to navigate and eventually to overcome.

The Strategies: This was the child with whom we figured out how to remove learning disabilities. Seeing that he did not have the formula necessary for reading, for 6 weeks we focused on gradually building up the foundational skills that are required to recognize and recall visual patterns in the form of sight words, and did not ask him to read, so that the trauma could recede. This included a carefully-scaffolded series of movement-based games that gradually taught his brain to pay attention to visual information, to flexibly group and regroup that visual information, and then, overtime, to recognize words as combinations of shapes. Six weeks later, his mom caught him under the covers after bedtime, reading Harry Potter by flashlight.

Favorite Project: “How can we design a “tiny house” to meet the needs of a real client?”

Grade Level: 1st grade

The Success: Within their public school environment, he had been isolated to a resource room with a paraprofessional to manage what the data report revealed was 3-10 refusals or aggression each day. On day 1 we saw much the same. We started day 2 with our social-emotional curriculum, tailored to the analytical strengths of gifted children, and watched him transform before us into a model student and social leader who was attentive to the needs of staff and peers alike, albeit with a side of mischief.

The Obstacles: This child’s dramatic response to our social curriculum indicated that he had a real difficulty understanding how to meet behavioral expectations in his prior setting. The significant experiences of seclusion and restraint had left PTSD triggers, and yet despite these fears and the social gains under our curriculum, we still saw a reflex to become disruptive if he was given a learning or social task demand that combined motor and cognitive skills, like reading or jumping while reciting the alphabet.

The Strategies: This child responded immediately to our social curriculum’s focus on how to foster a community of peers rather than on how to avoid getting in trouble. Yet we still had to address the learning-based PTSD triggers to make progress in the classroom—and that demanded giving him hope that he could in fact improve in the areas where he was struggling academically. When we gave him coaching in how to understand his own neuropsychological profile and the hope that comes from learning how we can change that profile through neuroplasticity using the unique, research-backed approach developed at Cajal, he was on board, met or exceeded academic and behavioral expectations and modeled gratitude for his older peers.

Favorite Project: “How can we create a robotic sculpture that provides a visual display of how vibrations from the Norwalk Bridge construction project impact animals native to the Norwalk River?”

Grade Level: High School

The Success: School had felt like an alienating place for a long time by the time this student found his way from Brooklyn to our school, which was located all the way up in Fairfield at the time he joined us: a full two hours each way that required a 5 block walk, a subway and a ride up Metro North. Nonetheless, within a matter of weeks, this student achieved full participation and attendance, and began to dig into his gifts and, critically, understanding what had made them difficult to access in the first place.

The Obstacles: Independently managing a two hour commute each way on public transit demanded substantial energy, problem-solving and independence—and then on arrival, the real work began, to disentangle the asynchronous skills that had made school dissatisfying in the first place.

The Strategies: Tapping into his expertise in neurophysiological components that can keep kids feeling locked into school refusal, our neuropsychologist provided daily counseling sessions via Zoom to help him take that essential first step out the door on days that school felt like simply too much. On arrival, we used our project-based learning to meet him at the door with intellectually-stimulating, discussion-based instruction that piqued his interest and kept him coming back for more.

Favorite Project: “How can we design a device that can monitor core body temperature and then either heat or cool the body to maintain optimal thermoregulation?”

The Success: Being named Captain of an elite-level community athletic team “because of the way he welcomes all the children in” after leaving the public school environment secluded and denied opportunities to progress athletically because of social difficulties.

The Obstacles: A rare, undiagnosed receptive language disorder and neurophysiologic dysregulation driven by a complex medical condition undermined his ability to parse and respond to directions and social cues, while the medical profile undermined his ability to maintain calm in the face of these frustrations. All of these challenges were further exacerbated at school, where orthographic processing and dyscalculia further undermined his confidence, and where well-meaning behavioral interventions for what was in fact a complex interplay between a learning and a medical disability had led to shame and school-based trauma that further undermined the self-regulation that is essential to effective social interactions.

The Strategies: Our expert clinicians gradually connected the dots between the unexpected areas of difficulty in the midst of a strong cognitive profile, creating new testing methodologies where no normed testing instruments were available on the market and gradually isolated the difficulty down to a “partial Gerstmann syndrome” impairing his ability to assign language to temporospatial concepts, with wide-ranging social and academic impacts. Using our Neuroplasticity Interventions, we gradually built up the neural network required to perform this essential skill, and then tailored social cognition instruction and math curriculum to improve academic and social outcomes while work progressed to enhance this essential neurocognitive skill. Meanwhile the “4 Columns” code at the heart of our community culture and social-emotional approach emphasized the value of being of service to others: a less complex lodestar for kids with complex social cognition learning.

At the same time, our physio therapists and clinical neuropsychologist worked closely with his neurologist and immunologist to isolate connections between hidden medical events and observable regulatory difficulties—and then built up the enteroception and other physio skills he needed to independently self-monitor, self-manage and self-advocate for those needs.

Applying all of these strategies in concert brought gradual social progress within the school setting, but translating that success out of school and onto the playing field required a full court press. In-school counseling helped him to process the emotional impacts of his unique journey and teachers built up his confidence during physical education classes that turned into spirited-yet-friendly competition. Communication between home, school and a series of coaches to explain his unique language profile gradually opened up higher and higher level playing opportunities. But at the end of the day, it was his own grit and commitment to lifting up others through actions sitting squarely in what we call “Column 1” (the goal) that catapulted him past social acceptance to social recognition as the leader that he is.

Favorite Project: “How can we create a theme park with scientifically-possible roller coasters?”

Grade Level: Transitions Program

The Success: This profoundly gifted student had already attended a year of college before coming to Cajal. There, he had struggled with the executive function and social demands of college and independent living. In his interview, he asked for permission to teach the other students and do his own projects; we explained that that would defeat the purpose of learning how to connect as a peer and to bring his brilliance to tasks outside his interest areas. One year later, he was doing both.

The Strategies: This student was so strong in his analytical abilities that motor coordination, visual processing and social development had simply gone by the wayside in his pursuit of more intellectually-fulfilling activities. Thus, the gap between his social, emotional, study and daily living skills and those of his peers grew wider each year. We gave him the data and primer in neuroscience that he needed to understand (and therefore not hide from) the ways that his “Not Yet Skills” impeded his progress, and used sitcoms as academic material that could be analyzed, guiding him to derive his own social understandings through the critical thinking skills where he excelled just as one would in a history or literature course. Soon, he shifted from blocking out the non-verbal communications that had previously been little more than signal noise, to noting and responding to them with peers, who simultaneously shifted from colleagues to friends.

Favorite Project: “How can we envision a democratic community in the years 1202-1204 in Normandie, France?”

Grade level: Middle school

The Success: In September, they retreated to a closet at the first sign of academic challenge or social disapproval. In June, they knocked it out of the park at sleep away camp in a bunk with 30 other kids.

The Obstacles: Intense reactivity to sensory inputs and sudden neurochemical releases triggered by idiosyncratic medical events made it difficult to maintain calm in the face of academic and social anxieties. Add to that dysgraphia (a fine motor coordination difficulty) and an absolutely brilliant mind, and you find yourself with a mash up that was simply too much to bear.

The Strategies: Piece by piece, we helped them learn to self-monitor, self-manage and self-advocate for their sensory and immunological needs, and to find patience for their own learning journey. Helping them understand their motor difficulties—and plugging away through occupational and physical therapies to address them—brought increasing confidence and eventually a bubbling joy as they approach learning as an adventure in which they are now confident they will succeed.

Favorite Project: “How can we create an app to spark an international revolution for climate change?

Read in-depth case studies from our blog

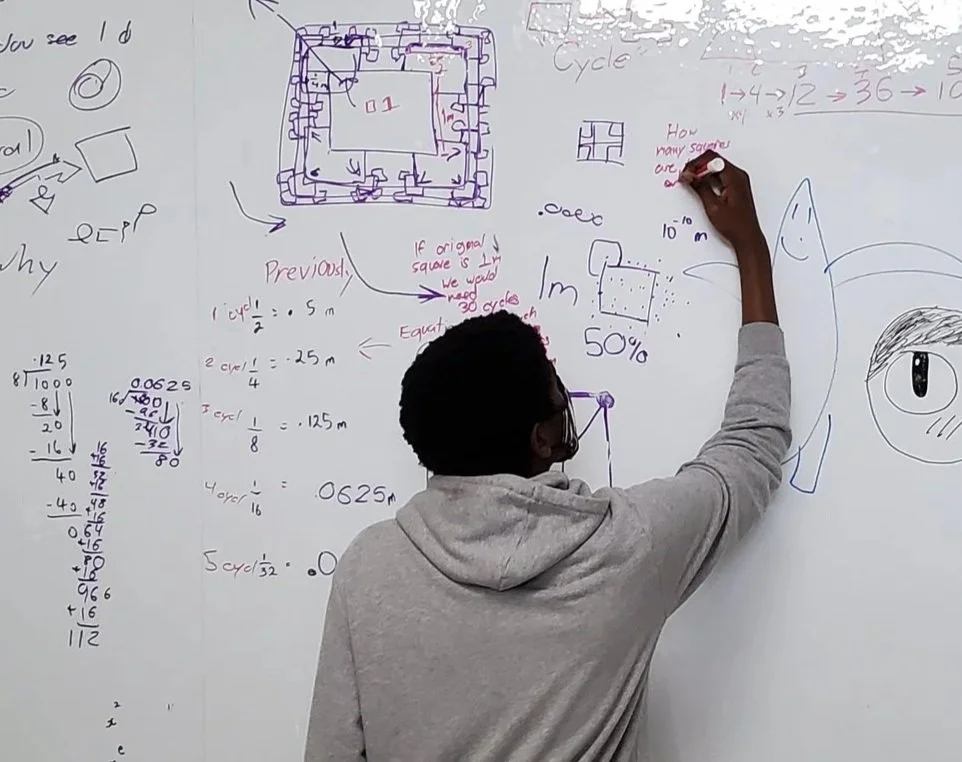

Academic skills from math to alternative energy sources came together with executive function, fine motor and social skill therapies in our Tiny House project. Read our case study to find out more about how we are adapting the project-based learning framework to incorporate therapeutic programming!

Find out how data-driven, individualized instruction helped changed one child's relationship to math from "I just can't" to "wow I'm good" when his teachers removed all the language and digits that were getting in the way--and then used OT strategies to built up those capacities, through neuroplasticity.