Why accommodate a learning disability if you can remove it?

Cajal Academy’s ground-breaking approach doesn’t accommodate children’s disabilities—it removes the skill deficit that drives them.

Since 2019, Cajal Academy has developed a first-of-its-kind approach to reducing and in some cases eliminating learning disabilities, by using task-driven interventions to build up the neural network the child needs to perform the many discrete skills that they need to perform those learning activities.

This ground-breaking approach, developed at Cajal, builds on the well-established scientific principle that the human brain is constantly rewiring itself as we learn: a principle called “neuroplasticity.” In other words, whether at school or in the course of our everyday activities, our brain isn’t just acquiring new knowledge and information within the confines of its current infrastructure. Rather, it is constantly reallocating resources within that infrastructure to remove resources (neurons) from the networks we need to perform tasks that we are no longer doing, and to add resources to the networks required for the tasks that we use frequently.

This has huge implications for general education, and even bigger ones for special education. For starters, it means that each child’s skills are not static—and thus that learning “disabilities” are not immutable. Rather, they can be developed through an intentioned approach to (1) identifying which specific neurocognitive “splinter” skills are holding the child back and then (2) building up the neural networks required to perform those skills by being strategic about the tasks we ask that child to do.

Equally important though, this means that when we instead accommodate a child’s “disability” through supports that remove the demand to use that skill, we may actually make the problem worse—because as we reduce the demand for that skill, the brain will reallocate those neurons to other neural networks.

Getting behind the diagnostic labels to figure out what’s driving them: a data-driven process

This work is inherently detail-driven. Traditional special education approaches start from diagnoses like “ADHD,” “dyslexia,” “dyscalculia,” “ASD,” etc. These labels are given based on checklists of symptoms in the DSM or diagnostic statistical manual: checklists that were derived through a statistical analysis of what different psychologists are referring to when they use a particular diagnosis label. But this doesn’t tell us what’s driving that presentation. Thus, it only tells us how to accommodate the problem—not how to solve it.

At Cajal, we take a new, neuroscience-driven approach that delivers actionable insights we can use to reduce those challenges themselves. We start with the actual performance on learning and social-emotional tasks, and then we dig into the data in the child’s neuropsychological and neurophysio assessments to identify in which of the several discrete neurocognitive skills required to perform those tasks does this child lag behind. Using well-normed assessments and our team’s high level of expertise in understanding what combinations of skills you need to perform a given task, we identify which cross-cutting skills are holding back their performance across a range of academic and social skills and then fashion a carefully scaffolded series of tasks requiring the brain to engage in that particular thought process—so the brain applies more neurons to the neural network required to perform it.

In this way, we are rewiring the child’s brain to apply more resources to those skills they need most to progress. Over time, the struggles in the classroom, and the diagnostic labels that described them, are removed, preparing the child to go forward with a broader array of settings and tasks in which they can be successful.

Changing the Learning Curve

Traditional special education approaches deliver consistent, incremental growth in the child’s ability, but they don’t reduce the underlying discrepancies in the learning skills that go into performing that skill. For students who have large gaps in their neuropsychological profiles, as is the case with the twice exceptional students we serve, this does not solve the core problem underlying their academic and social-emotional difficulties—namely, the gap itself.

With our Neuroplasticity Interventions, we see a fundamentally different learning curve. Student growth in the targeted task initially remains flat, because at that stage we are working to reduce the foundational skill deficiencies and are reducing demand for the combined task through differentiation in order to give the child respite from the conviction that they “can’t” perform a given task and the ways that this academic trauma impairs their skill access and growth mindset. However, once those foundational skills have been improved we see a hockey stick shaped growth curve, as the gap is filled and the child is able to approach the composite task at their now more evenly high level of skills. This can make the difference between, for example, learning to read and reading for pleasure.

Transformative results in children’s learning—and in their lives

We have now successfully applied this process to a range of challenges, from reading and writing disabilities to organizational, social-emotional and math difficulties, with often dramatic results.

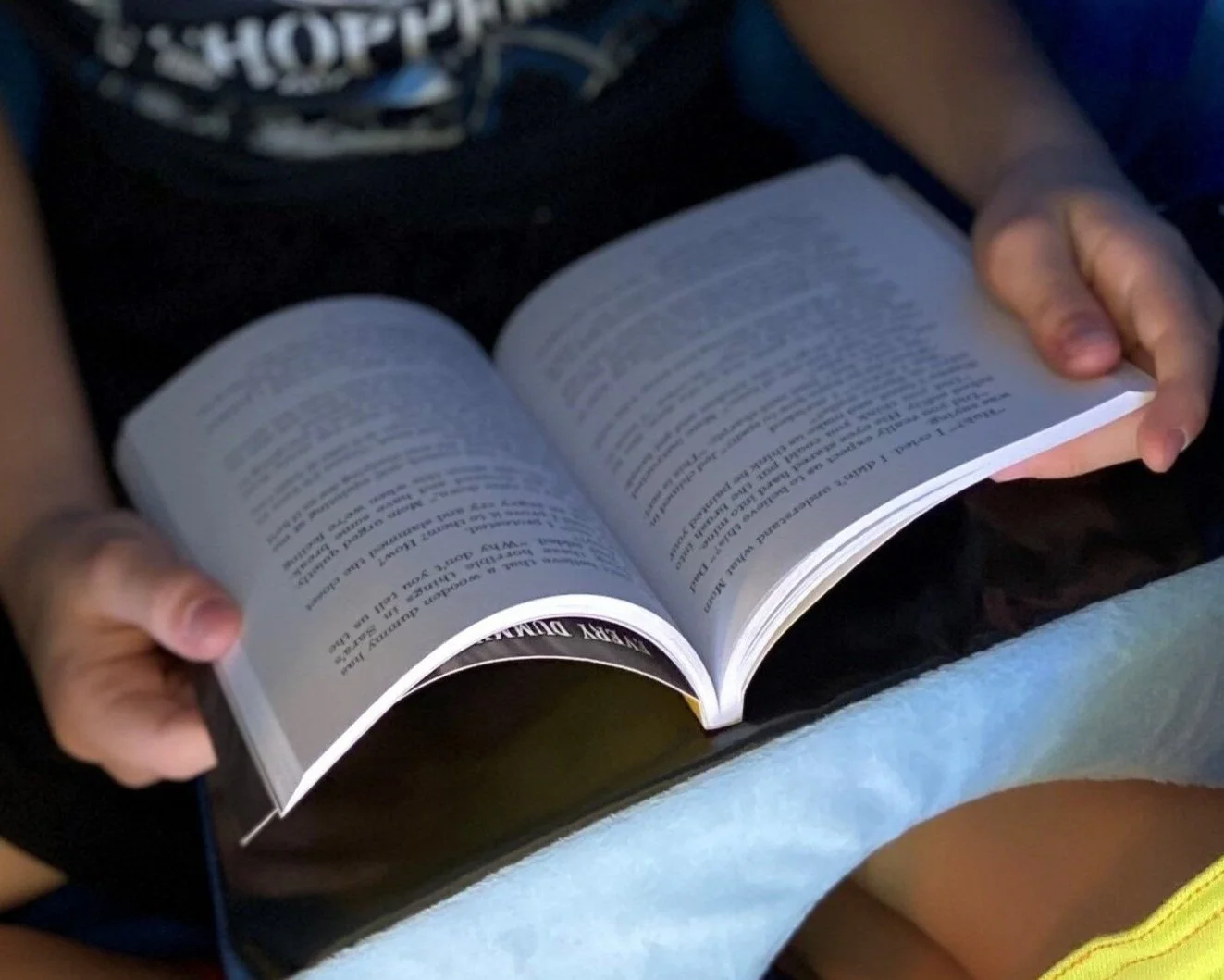

The brilliant middle school student who could not independently read more than a paragraph without losing track of what the words even mean, or write more than his own name without someone spelling it for him letter by letter in September—and was independently reading 45 to 60 pages a week in February and independently writing a short story while he typed it in April.

The second grader who was several grade levels behind in reading who was described as lacking in “motivation” but who was reading several grade levels ahead just six weeks later—after we discovered that his visual processing challenges were interfering with his ability to retain and recall what words look like: an essential skill for reading.

The hyperlexical nine year old who spoke with the vocabulary of a college professor but curled up in fetal position under his desk when we asked him to write because when he tried to write his brain went blank, who came to see himself as an author after we identified that his difficulties with motor coordination were taking all the neurocognitive resources he needed to perform the skill.

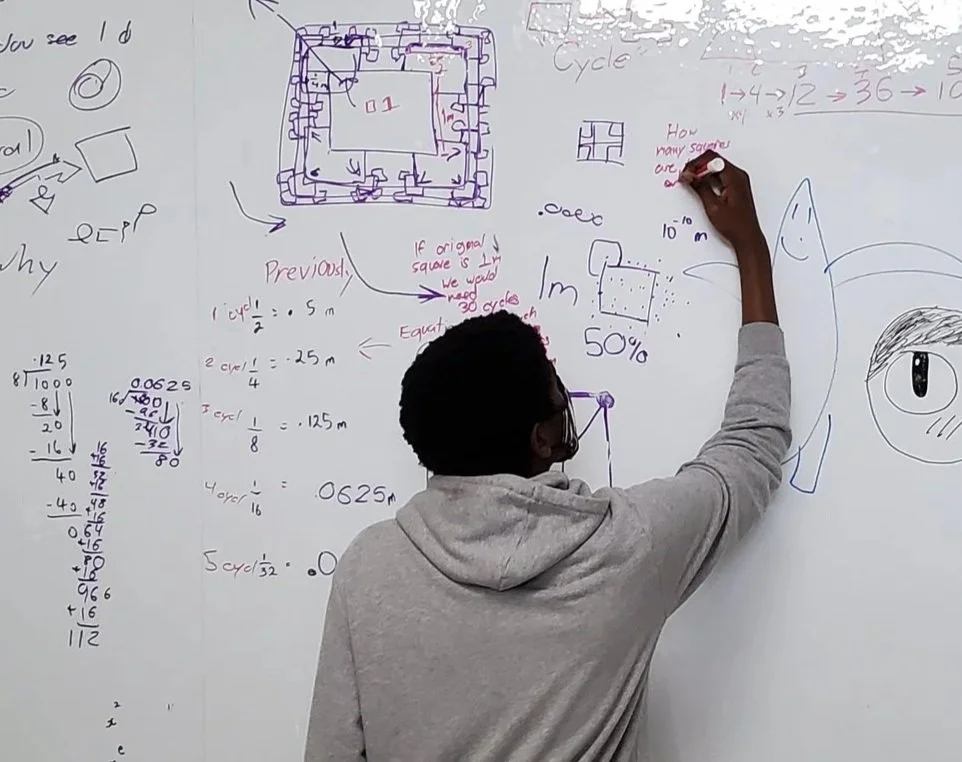

The middle school student who was unable to do basic addition and subtraction but who could draw and make music at an elite level (and thus clearly “understood” math) who broke through once we identified his brain was not retaining sequences, without which one cannot add—or properly parse social feedback, comply with oral directions or many of the other areas where this child struggled.

The profoundly gifted high school student who eschewed movies as “boring” and never felt he fit in or knew how to connect with others, but who started to understand and respond to nonverbal communications after we identified that he wasn’t picking up the salience of visual content and provided a bespoke curriculum (using TV sitcoms as our course material) to academically backfill his knowledge base of how changes in facial expressions correlate to different human emotions.

As these students have made these breakthroughs, we have seen our children transformed not just in their scholarship but in their understandings of themselves. We couple our interventions with growth mindset coaching, to help them find the courage to try the tasks they had previously found difficult and thus to discover what they can now do. We also share the science of neuroplasticity with these highly-analytical kids, helping them to understand that we all have areas where we struggle and others where we shine—and that that’s “just science.” This provides a powerful counter-narrative to messages they may have absorbed on the playground that they are are “bad” or “stupid,” while also fostering a new, science-based understanding of the great diversity of the human experience: understandings that form the basis for our leadership skills curriculum as well. Together, this approach reduces and heals the prior school-based trauma that impacts so many twice exceptional kids and other complex learners, thereby setting them on the road to independently chart their own course for the future.

Here are just a few of their stories:

Only at Cajal Academy: the First Neuroplasticity School

We are unaware of any other school that is approaching special education interventions in this way. And yet, this science is not new. What is new is that we have developed a research-backed methodology and a new educational model that we call a Neuroplasticity School for applying that science in a way that moves students forward while reducing the costs of meeting their educational needs.

Contact us to find out whether your child might benefit from this process and approach, and whether Cajal Academy might be the right fit for their needs.